What a frustratingly delicious and maddening rollercoaster ride this novel was. Feyi when I catch you?! This was a page turner for sure, but because it was a library book, I couldn’t mark it up as I went along so instead, I am going to go through some of the questions in the book club reading guide, as a means to reflect on my experience of it.

Q: Feyi’s interior monologue (and actions) In response to Nasir’s pursuit rapidly oscillates between interest and disgust, as we see in chapter 2: “he was hunting her”; “she wanted him closer. She wanted him far, far away.” What does Feyi want on the roof? Do we know? Does she?

I think she carries enormous guilt about the fact that she not only survived the accident with Jonah, but is now at a place where she is physically and emotionally trying to explore new connections. Feyi is on the roof because she is really curious about Nasir, but also knows she can’t make eyes at him ‘during the people’ (South African turn of phrase, look it up, or don’t). So she knows they can have a private moment up there.

Q: In chapter 3, Joyce says, “Maybe Nasir is it—not the serious thing itself, but just the chance. Don’t run away from it,” in response to Feyi’s insecurities about accepting a date with Nasir. Later, Joy’s voice in Feyi’s head tells her to take a chance. What does this chance refer to and what could it mean will Feyi?

A chance at a real romantic relationship, what she has with Milan is purely physical but she can already sense that things would be a lot more serious with Nasir.

Q: When thinking about her developing emotional intimacy with Nasir, Feyi considers the fact that their physical intimacy is moving glacially. In chapter 4, Feyi asks Nasir whether he was sleeping with anyone, and his response allows for a shared moment of trust and humour between them. Nasir uses that space as an opportunity to inquire about Feyi’s studio. How does this reflect their respective outlets of intimacy and their inevitable relationships to it?

There’s a quiet acknowledgement that Feyi isn’t quite ready for physical intimacy because Nasir is ‘more’ than just a guy, knowing that he is being ‘serviced’ elsewhere brings her some relief that she can push that task even further out (emphasis on task). I remember taking issue with how this conversation moved on so casually, flippantly almost. But I recognise that is because I hold a candle for Nasir and I was upset that he was stepping out on us 🥲😅 The pivot to the studio conversation is his effort to get to know her more deeply, he is at this moment operating under the premise that she wants to be known fully before taking their relationship to the next level. Oh, if only he knew 😦 Shame I’m being unfair she also was giving their relationship a genuine chance at this point, but definitely holding back A LOT under the guise of taking things slow.

Q: “So much of her time was spent in uncertainty” Feyi reflects on her imposter syndrome; meanwhile “It was hard to imagine Alim ever doubting if he fit into whatever he was.” What were Feyi’s doubts around her work? How does this doubt pervade other aspects of her life and how does she view Alim’s sureness in comparison?

Because her art is so personal, it puts her life up for scrutiny and judgment from others and herself. It operates as a mechanism to memorialise and process, which requires enormous amounts of vulnerability from her, which she isn’t entirely comfortable with. Alim is able to practice his art more freely because he is more open and quick to vulnerability, it colours his world as opposed to dimming it in hers.

Q: “It was something she wanted to hear—what it was like to fall in love again after your heart had been shattered. She could feel Jonah’s presence on the mountain peak, gentle and curious,” writes Emezi in chapter 10. How does this differ from past moments of intimacy up until this point, when Feyi felt Jonah’s presence?

In other moments, she was overcome by guilt, and Jonah’s presence was her internal warning signal that what she was doing was not ‘right’. When she is on the mountain top with gramps (sorry, not sorry #justiceforNasir) because she feels strongly for and about Alim, she doesn’t feel that guilt and/or shame; instead she feels the warmth of a familiar safety and calm by being with someone who makes sense to her.

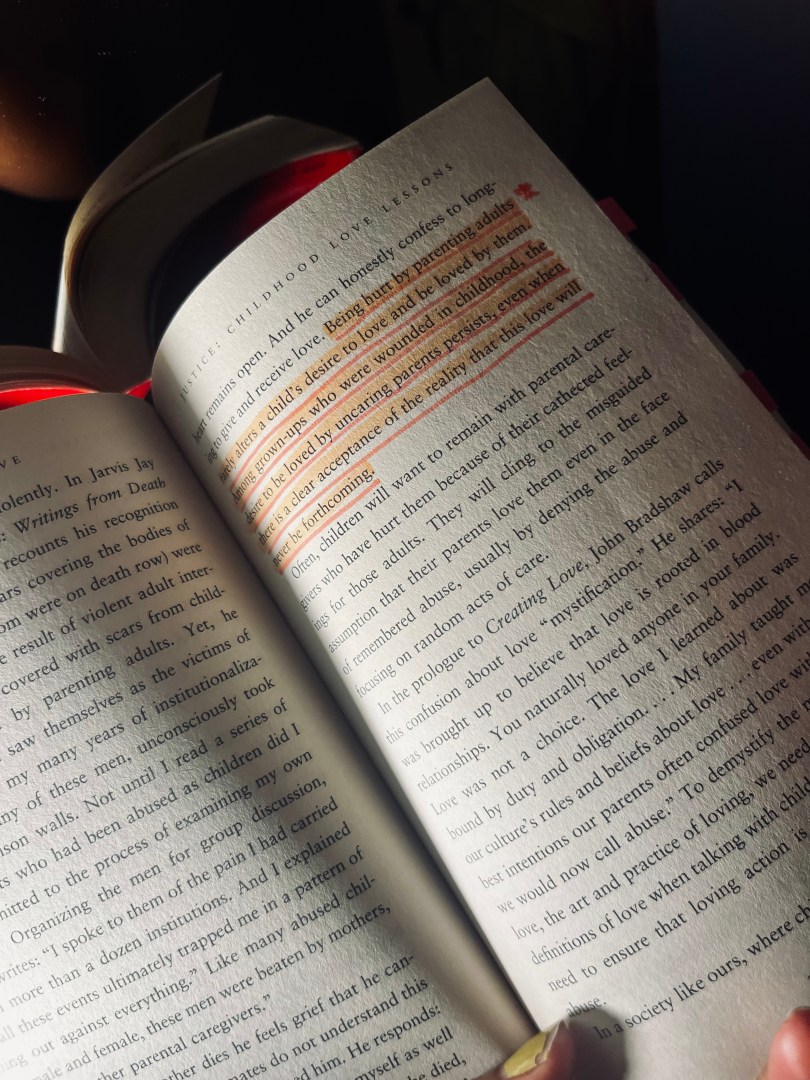

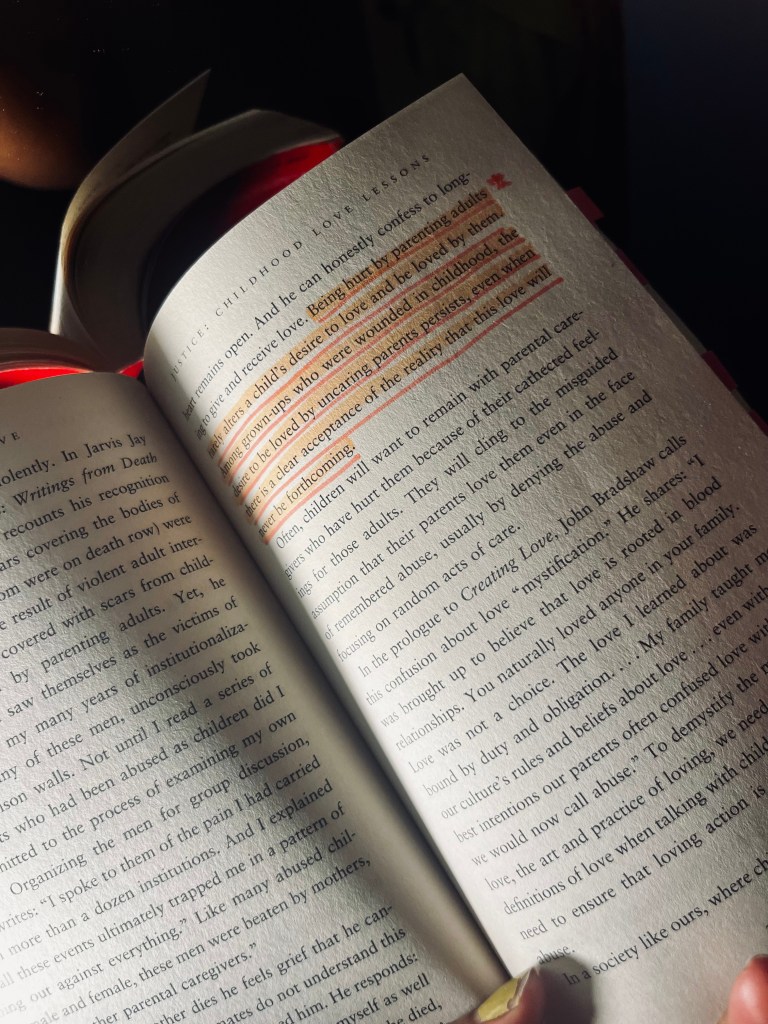

Q: “’ There are so many different types of love, so many ways someone can stay committed to you, stay in your life even if y’all aren’t together, you know? And none of those ways are more important than the other,” Feyi says in Chapter 11. Why is this perspective liberating for Feyi?

I think she realises that moving on isn’t about forgetting Jonah, that being devoted to his memory doesn’t have to mean staying stuck in her hurt or even in who she was when they were together.

Q: In Chapter 11, Nazir tells Feyi, “Lorraine and I don’t have a lot of memories of our mum. The house helps us remember.” What does this house represent to the Black family? And to Feyi? How do these meanings influence the space she occupies in it?

I think it is a living monument to the memory of what they lost and the effort to keep things together through physical reminders of what once was. It also signals an inability to move on in some ways, less nostalgia, more shrine if you know what I mean. Crazy to me that Feyi feels a pang of jealousy seeing family photos – like yes doll, where do you think you are?!

Q: Feyi fondly recalls Jonah’s words in chapter 15: “He said [being messy is] one of the best things about being human, how we could make such disasters and recover from them enough to make them into stories later.” How has this informed Feyi’s decisions in life since Jonah’s passing?

Well she’s made quite a big mess of things at the Black’s, so that’s one. This recollection allows her to remember that she can prioritise herself and her desires (not that anything had been stopping her to be fair).

Q: What is the difference between Alim calling Faye his friend and Faye calling Nasir her friend?

He meant it, she didn’t 💀

Q: “You know you can always just come home right?” Joy reassures Feyi in chapter 16. What or who is Feyi’s home here?

Joy is Feyi’s home now.

Q: In chapter 17 we witnessed the confrontation between Nasir, Feyi, and Alim. Discuss whether you expected it to go down this way or not. When Nasir’s anger and subsequent actions justified? Were Alims? How is this possibly triggering forfeit?

I actually did because I was BIG MAD myself, but I was also scared of him and what he might do in that moment, I understand why she was terrified too.

Q: Alim tells Feyi in chapter 18, “I can’t bring myself to not try to give you the best every year I have left,” to which she requests he make “no plans.” Why is Feyi resistant to making plans?

Because people can die tomorrow and none of those plans would matter, she has conditioned herself to live moment by moment because of the fear of loss that constantly walks beside her.

Q: “You can see [my painting] in any stage it’s in. I don’t care, I like showing myself to you,” Feyi tells Alim in chapter 21. How does this stark difference from her objection to showing Nasir her artwork parallel the differences in their respective relationships?

This really hurt me, because Nasir was so eager, on board, down-for-whatever, desperate for her to show herself to him. But she just couldn’t and I guess that’s only fair, we don’t have to match people’s attraction/energy/care, but I do think he was owed more honest communication about the improbability of her feelings for him growing beyond a homie level.

Q: “You’re worth it, Feyi. You can be yourself, as messy and contradictory as you like,” Joy affirms in chapter 5. “He’s lucky to even be near you.” Feyi’s feelings seemed to be at odds with each other throughout the novel. Speak to the inherent beauty in the contradiction and comfort and transients that come as a result of Feyi’s growth, both within our protagonist as well as from the perspective of the reader.

I struggled with her choices, not gonna lie, but I get them. She gave herself the chance to figure out what she truly wants and needs. She was ten toes about what she did and didn’t want for herself. I suppose the intensity of my disappointment helped me realise that people fiercely choosing exactly who and what they want for themselves might always look crazy or wrong or ill-timed to others, but that those things can’t and shouldn’t inform whether or not they make those decisions. That sometimes your body knows before you do what is meant for you and what isn’t. As much as I was batting for Nasir, choosing him would have been a betrayal of self that actually may have set Feyi back even further in her journey of healing. Alim, whether I like him or not, was the person she needed to help in coming back to herself fully and simultaneously shed the survival version that had been in the driver’s seat for the last few years (unfortunate pun, forgive me).

That said, #justiceforNasir, tell him he can find me @pheladi_s on all socials.