When the news broke that D’Angelo had passed earlier this week, one of the first reactions I came across online read: Mind you, I thought I would’ve had a first dance to “Nothing Even Matters” by now! (a post by @yasistatorrian). To which I replied, “Oh girl, same”. The deluge of grief and love for D’Angelo that filled my timeline and inboxes this week has felt like a communal catharsis. The sadness of the loss was overridden by the reminder of his deep love of self and the other.

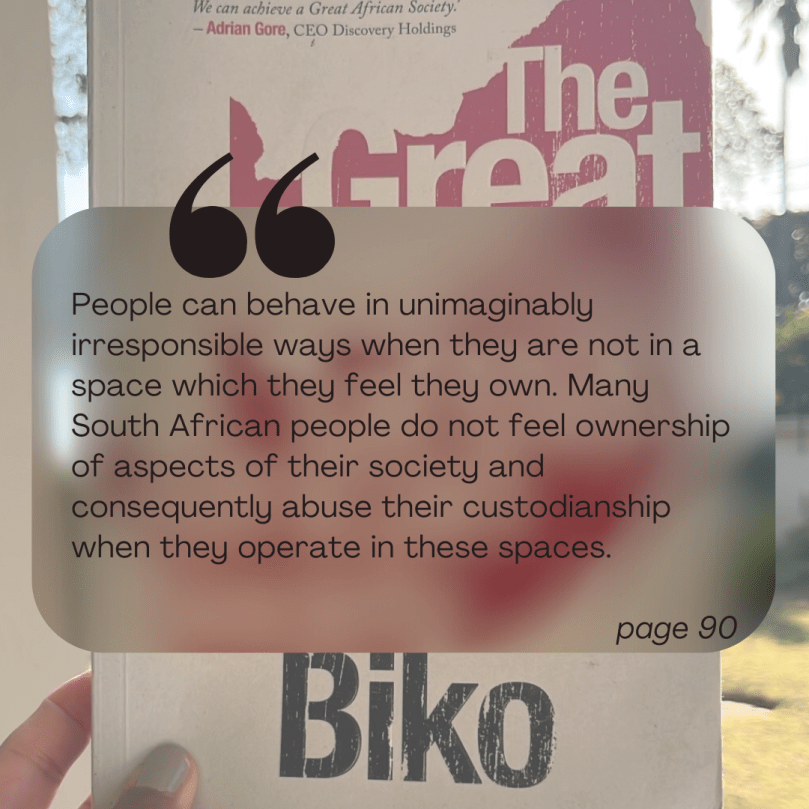

Like millions across the world, my first encounter with D’Angelo and his work, was through Untitled (How Does it Feel). I was very young, too young to understand the lyrics, but seeing the music video on a late-night music show on SABC 1 stayed etched in my mind. Some months later, a performance of “Send it On” and “Sex Machine” with Tom Jones on VH1, prompted me to rip the below poster from the middle of a magazine, risking judgment from my Catholic parents, sticking it front and centre on my candy white bedroom wall. At just 9, turning 10, I still didn’t grasp what the man was saying, but my ears and eyes were in agreement about his sonorous and physical beauty.

The music itself was dripfed to me in the years that followed during our weekly Saturday morning and afternoon spring cleans. My brother hogged the CD player, blasting Brown Sugar and Voodoo back to back. The VH1 live performance would also join the loop, it had been recorded via our VHS machine. We actually watched a lot of live music that way, as a family over the years, now that I recall. It was only when I got my own CD player in high school, that I could start listening to and reading through lyrics on the album sleeve of Voodoo that I began to hear beyond the melodies I had grown an affinity for over the years. Finally, stretching my understanding past just “di D’Angelo” (the South African reference for his undeniable Adonis belt), into the depths of his music. For the first time, I heard what yearning sounded like from the mouth of a black man and not the page of a Jane Austen novel. I heard what sounded like the celebration and reverence of black love, a welcome intervention for a black girl who was one of only 6 in her grade, listening to Avril Lavigne and reading Saltwater Girl (quite seriously at that).

“[He] made a kind of sound that made a house for black folks to live in. Under the sound of D’Angelo’s music, our bodies would wake up to who we have been… He made the ancestral close and intimate and sexy.”

Michael J. Ivory, Jr.

By the time the masterpiece that is Black Messiah came out, I was a long-skirt-All-Star-wearing-Africa-tattooed-dreadlocked-girl, in no need of saving. When it came out, I promptly bought two CD’s, one for myself and one for my brother, so we would need not fight for or ration out our repeated listenings. Three short months after it came out, Kendrick Lamar’s To Pimp a Butterfly came out, and that perfect pairing of love, politics, history and torment would be the soundtrack to my long car rides between Johannesburg and Pretoria that year.

We are bereft but blessed to have lived in the same time as him, to still have access to his work and thus pieces of his heart and mind.