When weeks of having Olivia Dean on repeat, collided with immersion in the words of bell hooks and Kennedy Ryan.

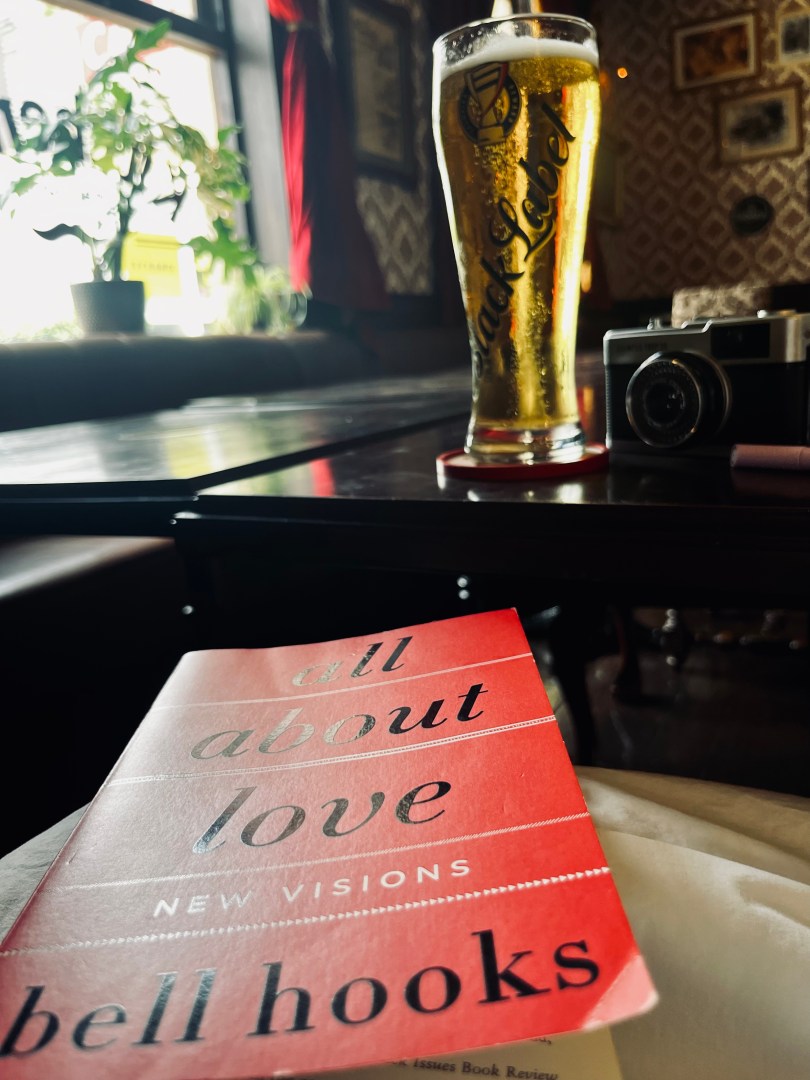

Working towards a ‘love ethic’ in a reality riddled with genocide, seemingly unchecked evil of all shades and material and spiritual poverty, can seem almost impossible. But rereading bell hooks’ all about love, provided the grounding I needed after being swept up in Kennedy Ryan’s steamy romance,This Could Be Us and all the while being serenaded daily by Olivia Dean’s affirming album, The Art of Loving since October 2025. They texts were connected and timely in a way that went beyond coincidence for me. I will attempt to synthesise some of the overlaps across the three projects that have left an indelible mark in my spirit.

Love yourself

To me, self-love is at the root of all three works, not the magical thinking kind that instructs: ‘love yourself before anyone else can’, but the kind that posits that an awareness of self and directly addressing patterns and behaviours that have informed past relationships. An exercise which then allows us to communicate more honestly and choose partners based not on our traumatic inferences and wounds, but our shared commitment to mutual growth.

When we understand love as the will to nurture our own and another’s spiritual growth, it becomes clear that we cannot claim to love if we are hurtful and abusive.

bell hooks, all about love, pg. 6

Of all the illuminating things hooks writes about love and loving, the thing that continues to stay with me is the idea that love is essentially rooted in care, choice, justice and nurturing one another’s growth, that the feelings it brings, the act of ‘falling’ in it, and any abusive betrayals simply stand in contradiction to living a life founded on a true love ethic. As intimate relationships often mirror or are informed by their immediate environment, a love ethic needs to underpin the broader society’s workings – a society moved by love rather than greed, violence and other injustices. But that is not the society and culture we live in.

Knowing how to be solitary is central to the art of loving. When we can be alone, we can be with others without using them as a means of escape.

bell hooks, all about love, pg. 140

In Ryan’s novel, the protagonist, Soledad, is forced into a journey of self-discovery by tumultuous circumstances, but quickly realises that her self-love or ‘self-partnering’ journey may require growing in love with another rather than practicing strict solitude rooted in denial of desire and care. It helps that Judah Cross (oh Judah Cross) is similarly trying to engage in a practice of prioritising self, through increased accountability, patience and intentional communication. And, the cherry on top, they both use all about love as a guide to work through this season and towards the other. Ryan is undoubtedly an incredible author, who manages to deftly marry romantic escapism with serious issues.

https://tenor.com/embed.jsI’ll be my own pair of safe hands, it’s not the end it’s the making of.

Olivia Dean, So Easy (To Fall in Love), track 5 on The Art of Loving

The Art of Loving as a whole, feels like a warm hug, reassurance that you are more than enough and worthy of effort (internally and externally). That the mistakes and missteps of your past aren’t defining, they are lessons that will help you communicate your wants and hurts with clarity. Dean’s self-love is rooted in radical honesty and staying true to oneself; a kind of reflexivity that allows one to honour whichever version of ‘love’ they are after. The yearning and care she speaks of are not rooted in melancholy, ownership but consideration.

Platonic love as vital anchorage

There aren’t enough sonnets for friendships. Note enough songs for the kind of love not born of blood or body but of time and care. They are the one we choose to laugh and cry and live with. When lovers come and go, friends are the ones who remain. We are each others constants.

Kennedy Ryan, This Could Be Us, pg. 95

We all know, or maybe have been, the friend who drops everyone and everything the minute they find themselves in a new relationship. Spending less and less time with their core support system, to maintain the newer, shinier connection that has entered their lives. There’s nothing wrong with making time to genuinely get to know someone and nurture what may be a more fragile connection. In our context, maintaining any relationship, romantic or otherwise, is made all the more difficult by demanding jobs, staying sane, fed and fit. But friendship isn’t an optional extra, a nice to have, it’s essential to living and loving well. Studies suggest that women’s friendships help us live longer, make us healthier and are most cases the only place we receive reciprocity and considered care. Obviously this isn’t a blanket fact or experience, some friendships (like relationships) are toxic or operate in misalignment, which would then bear very different results. So let’s healthy friendships are lifesaving for clarity’s sake. In This Could Be Us, this is evidenced by the way Soledad’s friends jump in to help her without question in moments of distress, in how they encourage her professionally and personally, and in how they hold her accountable. This accountability should, but doesn’t always translate in romantic relationships. hooks points out that for most women the stringent, unforgiving standards we have for friends, falls away when we encounter romantic partners because we are socialised to idealise the codependency of ‘other halves’ and put romantic love on a pedestal.

When we see love as the will to nurture one’s own or another’s spiritual growth, revealed through acts of care, respect, knowing, and assuming responsibility, the foundation of all love in our life is the same. There is no special love exclusively reserved for romantic partners. Genuine love is the foundation of our engagement with ourselves, with family, with partners, with everyone we choose to love.

bell hooks, all about love, pg. 136

Which is why the line, “who would do that to a friend, let alone the one you love” in Dean’s Let Alone The One You Love, is the one of the saddest for me on the album, it gives into that acceptance of elevated difference. In its solemn lament, it’s an illustration of the devaluation of friendship.

Love is in the doing

The desire to love is not love itself love. Love is as love does. Love is an act oof will—namely, both an intention and action. Will also implies choice. We do not have to love. We choose to love.

bell hooks, all about love, pg. 172

Something I have had to remind myself of, quite sternly at that, int the last few months, is that love is a verb, it’s a doing word. To say it is easy, to mean it requires more than the eight letters it takes to type it out. It’s the people who keep their promises, who show up, who consider you and who take any opportunity to demonstrate it in whatever way they can. I have also worked on being a better friend myself, it was one of my goals for the year, to prioritise my friendships and be intentional about their maintenance.

When conversing with the heart, expect it to talk back, to revisit the pains and disappointments that left the deepest dents and scratches.

Kennedy Ryan, This Could Be Us, pg. 216

The doing also extends to self responsibility and accountability – keeping the promises you make to yourself, committing to the routines you know you need, and truthfully engaging in introspection. The vulnerability on The Art of Loving acted as quiet confirmation that I was in the ‘right’ path insofar as my personal ‘doing’ was going. It more closely spoke to who I was becoming than who I was. It was a also a good reminded that you don’t ever really lose the love you have shared, especially if you shared it freely, and that helped me process a lingering hurt.

Love is never wasted when it’s shared.

Olivia Dean, A Couple of Minutes, track 11 on The Art of Loving