Some literature arrests us no matter who we are when we first read it.

We recently had a short discussion in our book club’s WhatsApp group about a local author with a new release. The reactions to the new work were mixed – a variation of “could never get into it”, “recall not enjoying X’s writing” and “enjoyed it at the time”. The last bit of last response stuck with me. It was mine, so I reflected on my own internal process of elimination when picking a new read, which sometimes includes being too old now, not being ready or not being the person I need to be yet.

I had this selfsame experience earlier this year, reading One Day by David Nicholls. I had just watched the Netflix series for a fourth time (to say I was obsessed is an understatement), so I figured the book must be better and it was February, the month Love™, so I dove in gleefully. It was an easy and quick read, but I only read on because of my now ripe love for the on-screen characters (actors more than the characters), not because I was drawn to the slightly annoying people I was meeting between its pages. The Dex in the book deserved a couple of right hooks if you know what I mean. The chasm between the relatability of the on-screen Emma and the Emma in the book was stark. But I knew that this had to do with 34-year-old me reading this work 16 years on, and not the book itself. If I had read it when it first came out in 2009, I would have been so taken and so seen by the literary iteration. Many parts of it would have mirrored my own experiences and possibly acted as timely foreshadowing. Now, it was just a confirmation of lessons already learned and squared away.

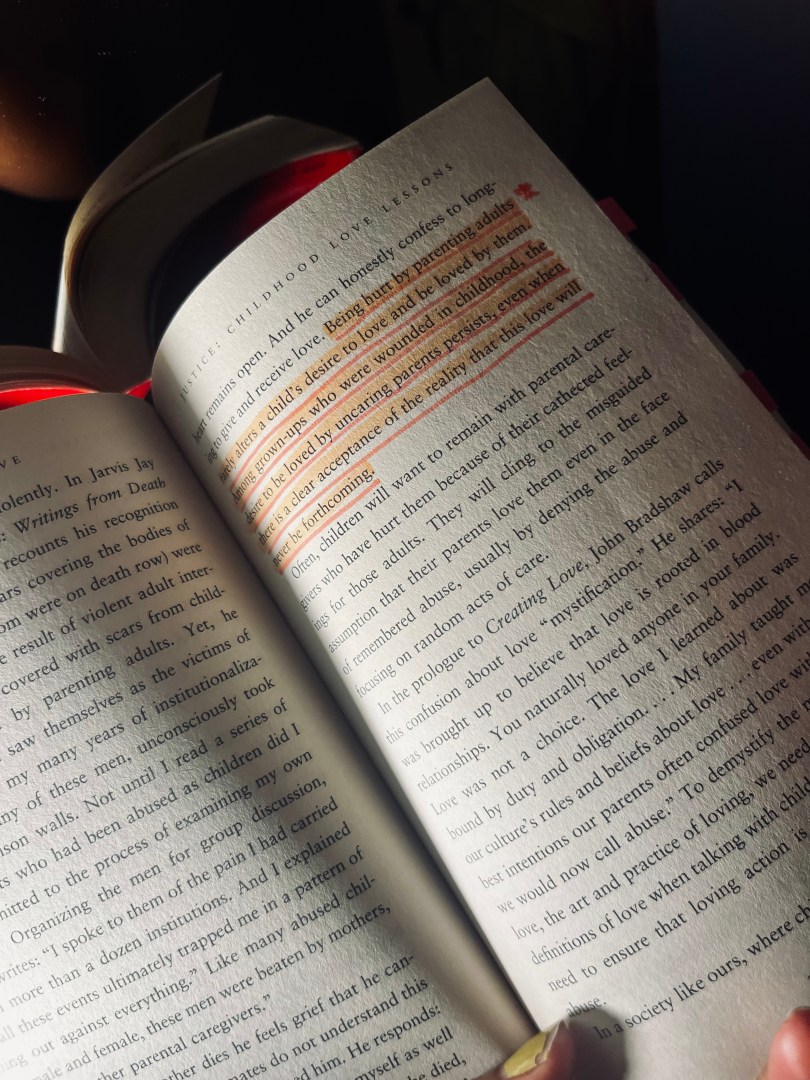

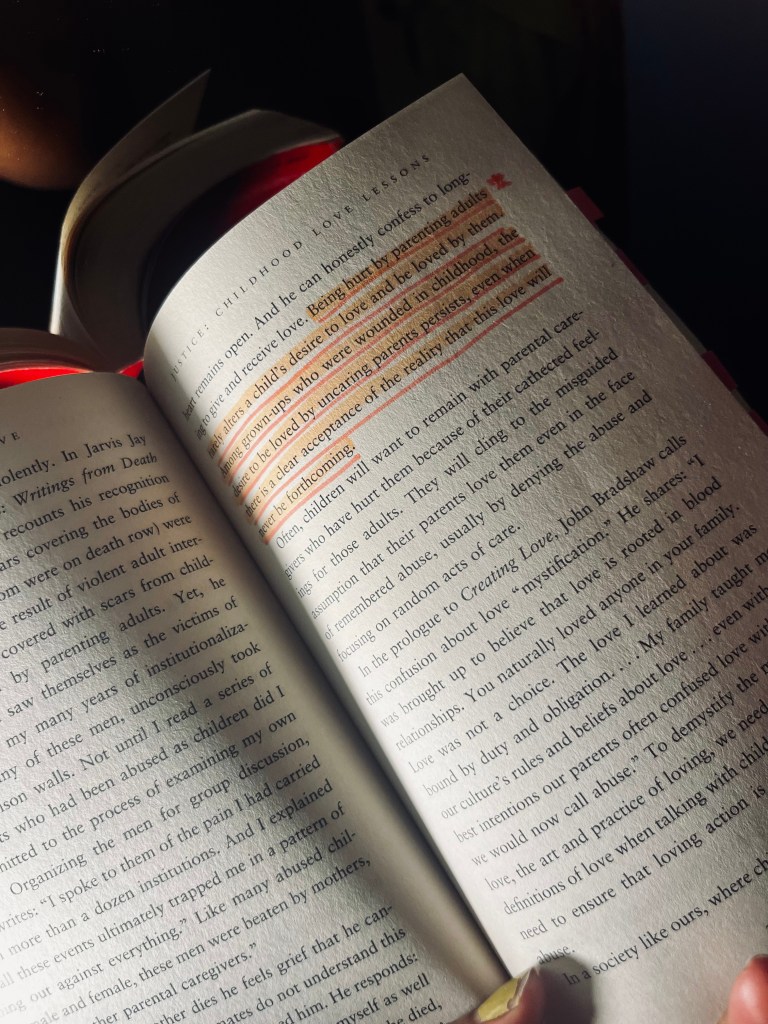

But the inverse was true when I finished a reread of All About Love by bell hooks just a few days ago. The 24-year-old teachings felt more relevant and timely to me now than they did when I first read it four years ago. Admittedly, I was a different person at the time. My reading was informed by the preoccupations, anxieties and vanities of that moment. Coloured by the somewhat small-minded motivations of the time, which were geared towards finding fault and fixing, rather than open-minded inquiry. I got to experience these two selves in the recent rereading through what I highlighted and wrote in the margins then, versus now. There was only one place in which my former and current selves overlapped in what they thought was important enough to highlight back then and again in this rereading.

This is not to say that what both readings did to and for me were not important, just different experiences of the same text because I was different, thus was my perspective. Which takes me back to one of the most instrumental and insightful quotes that echoes in the recesses of my mind years after my initial encounter with it as a second-year English literature student:

We don’t see things as they are, we see them as we are.

Anaïs NinAs someone who used to reread books a lot growing up, mainly because my personal library was tiny, this disjuncture was quite new. There are books I reread specifically because they take me back to a version of myself buried within the pages and emotions the text was initially received in, to revisit familiar and comforting characters, like one of the literary loves of my life, Velutha, from Arundhati Roy’s The God of Small Things or Tariq from Khalid Hosseini’s A Thousand Splendid Suns. When it comes to nonfiction like George Orwell’s 1984, or Steve Biko’s I Write What I Like, or Eusebius Mckaiser’s Run Racist Run, it’s an academic endeavour, rooted in brushing up or recalling in a theoretical way, not testing my present value system against the old, a remembering more than an updating of entrenched inner beliefs.

The timing of a read can be random, sometimes you are drawn to something simply because it’s in your eyeline or the cover is alluring. Or a friend or family member says “you must read this, it will change your life,” and the temptation of a life changed influences you. Other times you are pushed by guilt, a read that has gathered dust while watching newer, shinier books make it to the elusive bedside table despite the pecking order of the growing stack. Or you’re driven by a need to revisit a more familiar world. Or a looming bookclub deadline.The reasons are varied, but what I always find to be true is the person I am at the moment will dictate how I recieve the work or even if am able to take it in at all. In his paper, Why how we read, trumps what we read, Gerald Graff notes that “no text tells us what to say about it, that what we say depends on the questions we bring to it”. There are books like Pumala Gqola’s Rape, which I didn’t have the courage and heart to read six years after I had initially bought it. Books that I have to put down are rarely ever about what’s in them, but what’s in me. And then there are some outliers that no matter when I pick them up, an immediate put down soon follows *cough cough The Heart of Darkness, cough cough White Teeth, cough cough War and Peace*.Ultimately, that is the one of the joys of reading for me, the freedom to read what I like, when I like. To give a text licence to take over my life and mind for a few days or weeks. The choice is divorced from lists or the invisible place in the line dictated by when a book was purchased, but rather by the pull and capacity that lies in me at any given time. An acknowledgement of magnetic want and need.