A cyclical conversation rules the tl and fyp yet again – boys are still being left behind.

The congratulatory cheers and claps for the matriculating class of 2025 have been somewhat drowned about by the familiar lament of the year before and the year before and the year before, that says “good going girls, but why does your progress seem to be stifling that of our boys?” Less question, more accusation when reflected on from behind podiums and worried column space. Disintegrating and straying even further from the point when ‘debated’ in fragmented, ill-considered comment sections on social media timelines.

There was a lot of commentary that tried to contemplate the idea of boy children falling behind with compassion and care, but overwhelmingly there was also a lot of finger-wagging and blame levelled in various directions. Everything from absent fathers, red pill content, boy moms, patriarchy and hyper-masculinity were laid out as possible contributors by those discussing the matter out loud. What was absent on my timeline, was the voices and thoughts of men, particularly those not after engagement via rage bait, but those who grapple and internalise what our society is, based on their subjective experiences.

The scholarly insights from educational psychologists, researchers, teachers and those in civic society tell us that social conditioning, emotional repression, and the lack of positive role models are some of the core contributors. That ‘abandonment, marginalisation, and exposure to abuse’ make children even more vulnerable than they already are (Jaure and Makura, 2025). That girls learn to read earlier and this proficiency equips them with a better foundation than boys. That girls exhibit behaviours and social norms conducive to the current schooling system (Broekhuizen and Spaill, 2017). That a possible solution lies in socialising boys in ways that promote accountability and ‘positive masculinity’. These findings are widely accepted and valid. But I was interested to hear from those who had been either been groomed or spat out by the selfsame system, to briefly glean the past, present and possible future.

So I reached out to some of the men in my life to find out what they made of the growing chasm between boys and girls academically and otherwise. For context and transparency, these men are all 30+, black, some married, some single, some fathers, all employed. And I granted them anonymity, so they will be labelled Gent 1 through 4, respectively. This is what they had to say:

Boys live up to their unearned labels

There was a common thread between three of the four gents that spoke to one of the root causes being how boys, black boys in particular are regarded and thus treated straight out of the gate. Gent 2 said he grew up having to fight off labels erroneously ascribed to him. “If you were black and misbehave, like other kids, you would be labelled troublesome or problematic and that label would stick,” he shared. As a result teachers would be reluctant to help or invest in you because “uyahlupa vele” (you are troublesome). He added that seeing black girls and white boys and girls not experience this, meant that the label was internalised and leaving the door open to live up to it, especially when that was seen as cool/manly in later grades. Black men live in a society that “criminalises and infantilises” them, which deeply damages their personhood, added Gent 1.

The legacy of Apartheid, colonialism and capitalism

The “tragic fact” is that men continue to be taken out of the home for economic survival, said Gent 3. “We come from a history of broken households, the deep structure of the society of the past and a structure which endures today,” he said. This presents the obstacle of a positive role model who is present, and “successful” by virtue of employment, good habits and hobbies he said. But parents, where they are present, often don’t advocate for their boys early on or attempt to undo the social engineering which labels black men negatively, lamented Gent 2. The solve? “More employment and a bigger economy that is able to provide a bigger social safety net to support households, so they have a wider spectrum of options that influence a young persons early life,” said Gent 3.

A dollop of positive discrimination?

“Children exist in a world that they have very little control over,” said Gent 1, we are their custodians and need to correct any imbalances that present themselves. Speaking to the early-2000s ‘Take a Girl Child to Work day’ campaign, he joked that clearly that kind of empowerment is effective and could be used again. “Some positive discrimination is necessary for the boys right now, emotionally (speaking),” he said. He thinks boys need help with navigating and cultivating healthier inner emotional worlds. Gent 3 said investment in “other forms of expression” outside of sports is necessary, he thinks more diverse extracurriculars across the board is vital to showing boys that tapping into healthier alternatives.

Boys are lagging behind, not deliberately being left behind

Standing as an outlier, Gent 4 said: “Not only is the boy child being catered for, boys actually have a much easier and safer pathway through school than girls do. A girl’s journey through school is not only more dangerous, it is often more burdened. The girl child must do chores, fend off the advances of predatory men, exist in a world where men dominate leadership positions in every sector.” Girls’ academic advancement often means little in their professional and personal lives.

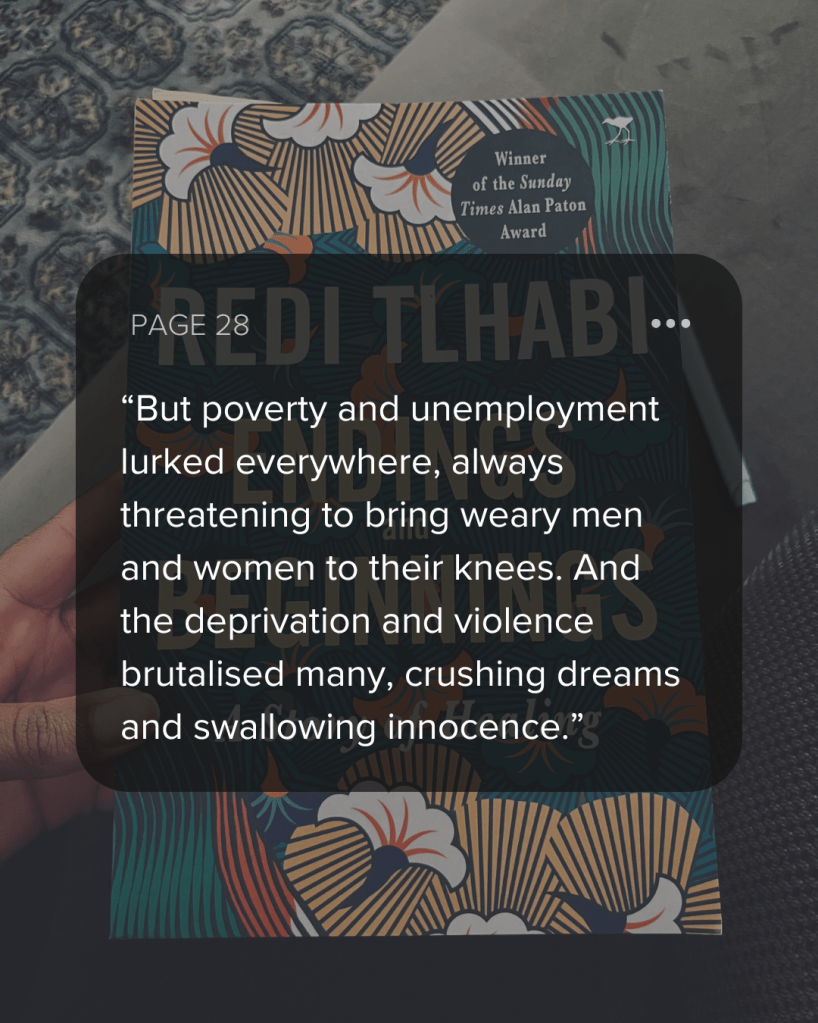

“Although South African women are better educated than South African men, they remain underrepresented in the labour market (Spaull and Makaluza, 2019), particularly in higher skilled occupations. South Africa is not alone. All over the world women have lower labour force participation rates compared to men.”

Rebekka Rühle (2022)

Alongside having to negotiate and fight through the gender pay gap, we routinely have to negotiate and fight for our physical safety and survival. So who is leaving who behind when the consequences are meted out against the supposed victors?

Role models are few and far between

For me, said Gent 3, the adult men I saw growing up were heavy drinkers, obsessed with chasing girls, hyper-masculine and lacked the “normal markers of success”. “They seemed happy and content in their pursuits, and this kind of example gets hardwired early on as being aspirational.

Gent 4 suggested that the deeper issue lies in toxic masculinity and the assumed spoils of adhering strictly to patriarchal scripts. “Toxic masculinity breeds complacency. The boy child believes that they can fall back on their future as a man with an easy path. Things like Forex trading, sports and content creation are seen as alternative paths to take instead of education,” he said. Thus, education as a viable path, has become optional. Not just in South Africa, but the world over. Making it big and quick through avenues like trading, content creation and others, drive boys opting out of education. “There seems to be this need to blame the failures of boys on some mysterious issue in our society or education system. The truth is that famous men are propagating anti-intellectualism on social media at alarming rates, and boys are responding in kind by not taking education as seriously as girls,” added Gent 4. On this point, Gent 1 was of the opinion that both boys and girls aspirations have been affected by late-stage capitalism and value systems driven by material gain over all else.

It was really refreshing to have these back and forth conversations with this small group of men, and it reminded me that much clarity is gained from slowing down to listen intentionally. This is a conversation and issue that deserves the appropriate attention because remedying some of the foundational issues that emerge early on, may be one way to root out some of the seemingly inevitable consequences that present themselves later on.