Last month’s bookclub read was Maame by Jessica George, which we talked at length about at the meeting so I don’t feel a need to write about it, but did curate some best bits below.

Last month’s bookclub read was Maame by Jessica George, which we talked at length about at the meeting so I don’t feel a need to write about it, but did curate some best bits below.

Slipping further and further from the light.

This week, I listened to an AI-generated voice recording masquerading as a completed university assignment. The initial task was for students to piece together a news bulletin for a radio show and record a voiceover for their script. At first, I thought maybe I had accidentally clicked something which started an automated reading of the student’s script. I paused. Went back to the beginning. Pressed play, and there it was again. A staccato mess, made up of ones and zeros, “reading” the script to me with all the flair of an instruction manual. I paused again. Surely not. Surely this student had not run their completed script through a programme that generates an AI voiceover. Surely. Why would a curious university student do that? No, why would a curious media student do that? What is the point of them being here if they don’t even want to hear the foibles in their voice, the rhythm of their own words, which should have been carefully constructed to fit into the three minute time limit? Then the take one, take two, take three and maybe take six of it all? “This is the end…” the line from Skyfall started to echo from a distant corner of my mind. Shit. This is it isn’t it? This is the new normal. Forget original thoughts, even original voice is on a slippery slope now.

“Where will we get our ideas?” – been haunted by this quote for months but I have been looking for three days and just can’t find the professor who posted this about a student of his responding to why they use AI to curate their assignments.

For some students, coming up with ideas and academic writing may be tough – and using AI may assist in getting an idea started or help refine a draft – that much or rather that kind of use seems somewhat justified to my mind. But subverting your actual voice, for whatever reason – not wanting to hear your own voice, not wanting to record your own voice or not being bothered to try – seems an incredible waste of an experience. One’s experience as a university student for one, particularly in a country where less than 10% of the total population even has access to a viable shot at higher education. Secondly, one’s experience as a creative (we all have the capacity and need for creativity/play), even more wasteful when your grades are embedded in playful and practical assignments that aim to nurture that trait, what could possibly push towards a machine-assisted “no thanks”? The chilling reality of it is that for many, critical thought and navigation are a chore to be avoided. While I recieve the point that people are overworked, overwhelmed and are just trying to get through ‘it’ as quickly and easily as possible, this seemingly convenient choice stands in the way of the kind of authentic grappling we all need for growth.

It brought back to mind a video clip I saw on Threads earlier that week, where the creator of an AI music prouction app was claiming that making original work takes up “too much time” and is “too hard” for the average joe to tap in to making music – “yes, it’s meant to be” was the welcome and resounding retort from people responding to the post. Their point being that the process of creation is meant to be developmental, it’s meant to be challenging and all the more rewarding when you ‘figure it out’, and the figuring out in this sense is a finding of oneself through that process. Creating anything worthy of reading, listening to or looking at requires this process. Perhaps what perturbs me most is that ultimately, I think the use of AI in the way mentioned above shows a level of disdain for what it means to be human. It considers the human brain as slow, unoriginal and ultimately not worthy of the effort/investment required to keep it vital through the exercise of reasoning, reading, failing and meaning making.

This is my second home video edit. Captured some of the things I got up to in April and May 2025, which included a book club meet, a walk in the park, a coffee date, a wine date, a cake decorating class and a potplant painting class for Mother’s Day. Wholesome time all around.

The fragility of life and the devaluation of individual lives in South African society swung on a pendulum throughout the 288-page stage that this memoir played out on.

For transparency’s sake, I must declare that I am a certified Redi Thlabi stan, she’s an incredible journalist and thinker I have always looked up to, and that no doubt coloured my reading somewhat. I picked my copy up at a recent book sale by publisher, Jacana, for a steal (one of those pay-per-kilogram sales – best!) Knowing Thlabi’s public persona quite well, I went in with quite specific assumptions about what her memoir might be like, and boy was I wrong on every count. Nothing could have prepared me for the twisted tale of a great first love marred by violence, manipulation and neglect. Sjoe, I was never ready shem.

Without giving away much more of the plot, I will say that the story that unfolds won’t be difficult to summon into ones imagination, Thlabi writes with a careful balance of honesty, warmth and clarity that transports you to the same street corners, the end of longing stares and swirls of despair that she experienced. It’s a reminder of how complex human beings and human relationships can be. Thlabi illustrates just how thin the line is between our precious inner lives and the relived realities that threaten it day and night. Grief stalks the pages from start to finish, the intensity of it varied from part to part and chapter to chapter, but ever present nonetheless.

Without being glaringly obvious about it, a geographic and historical profile of Soweto is sketched and helps root readers in place. The passage of time can also be seen through the lens of the location itself, ensuring that the past and present are delineated well. The lives of ordinary South Africans (and Southern Africans) during Apartheid always fascinate me, because they help us fill in the gaps that pure political and historical accounts can not. One of my favourite parts of the memoir was an account of how a central character risked life and limb to do his bit to assist in the anti-Apartheid movement. I appreciate accounts like this because the collective memory of our history can be narrow and solely focused on the people with bridges and buildings named after them, which is a distortion of how many truly played their part to fight off an oppressive regime.

Would I read it again? Nah uh. While intensely personal and revealing, I think it’s the kind of work that doesn’t necessitate revisiting when you are done reading it. Much like Khwezi, Thabi’s second book, it winds you so much that the very idea of bracing for impact again just doesn’t seem possible. But like Khwezi, it is a masterclass in using deep listening and authentic connection to navigate through one’s curiosity and sense of justice.

Some of my best bits below:

“Turn the lights off!” Before May 21, 2025 that phrase had much sexier connotations in my head, now, unfortunately, it is a reminder of the very strange ‘meeting’ between President Cyril Ramaphosa and that guy in the Oval Office. While I have appreciated and gobbled up all the analysis that followed that strange encounter in the last few weeks, something was still amiss. Memes, gags and retweets about the encounter, to be specific. This event was the first time I sincerely missed the bird app since deleting it from my phone last year.

Have I known peace, absolutely. It has been freeing to be rid of the watered-down, oft-triggering and anti-intellectual ‘discourse’ that had come to dominate my Twitter feed. Since the Musk takeover, the algorithm on that app has become most unhelpful and uninformative, making an occasionally toxic and divisive environment, perpetually so by boosting the accounts and thoughts of the most harmful actors in the swamp (himself included).

Anyway, that wasn’t the point of this little scribble. The point was, on that chilly Wednesday evening, I sat listening, enthralled by the shenanigans with no public place to live tweet and banter about the increasingly bizarre events coming through my speakers all the way from Washington DC. I was glued to the radio live feed in my car and couldn’t risk running out of the car, into the house to catch the visual feed in fear of missing even one second of the special episode of WWE. Itching to say something, anything, I turned to my almost inactive Threads account to cash in on the adrenaline that was coursing through me. I made a handful of posts, forgetting in my glee-come-horror at what I was hearing, to actually thread my posts together. But minutes passed with not a like, a retweet, a reply or GIF-only response. That’s when it hit me, that damn, Twitter is really gone and the live back and forths I had become accoustomed to during particulaarly important socio-political events and moments, could not simply be replicated on a different app. Sure, my following and level of activity on Threads probably plays a role, but that used to be the beauty of Twitter, you didn’t have to be ‘somebody’ to hop in on a trending conversation and simply by being vocal be seen by others interested in that conversation.

As someone who had been on Twitter for 14 years, using it professionally as a journalist and socially as a loudmouth, the relative silence during a live news event left me a little sad. Selfishly, for entertainment’s sake. But there was also magic in the way we collectively processed the world around us. As South Africans, primarily through laughter and making light of what is often too heavy. Threads did eventually ‘catch up’ the next day, filling my timeline with more post-meeting reactions, but the moment was gone, and my thumbs were at ease.

Took my new handycam for a spin at this year’s Franschhoek Lit Fest – a time was had 🙂

I know the internet girlies tell us we should never spin the block, but let me tell you that doesn’t count for books and the second or third or fourth time is often better than the first.

I first read Alain de Botton’s Essays in Love some eight or so years ago when I joined a new book club shortly after moving to Cape Town to start a new gig and life. I remembered laughing and nodding along a lot, so I decided to pick it up again when I needed a pick me up a while back. My slim recollection was correct, I laughed and nodded along more upon my second read. Time and one too many relatable experiences also made sure that I cried a bit too this time around.

As someone who often has to imbibe whatever can be learned about relationships through external media and anecdotes, the writing style in this book invited an intimacy which placed me in the middle of the room when they were fighting, alongside him on taxi rides and embedded in the neural networks that carried his stream of consciousness. De Botton allows us to be flies on the wall, inviting us into this relationship and its journey from start to end. With chapter titles like ‘The Fear of Happiness’, ‘Romantic Terrorism’ and ‘Psyco-Fatalism’ one is never too far from learning some cool historical and philosophical insights while relating to the more personal linkages. The numbered paragraphs in said chapters initially look like an odd choice but it actually helped move the narrative along quite neatly.

The critique of modern love and our strange passage through it remains my most memorable takeaway from this book; it is reflective and honest about what it takes to be with another person and highlights the inner conflicts that ultimately make/break such unions. Upon a second read, I probably like it more now than I did as the hopeful romantic I was when I read it some eight years ago.

As always, the best bits below:

*First appeared on Documentary Weekly on December 10, 2024.

Mother City by Miki Redelinghuys and Pearlie Joubert received its World Premiere at Sheffield DocFest 2024 and our writer Pheladi Sethusa had the chance to see it in Johannesburg during a screening hosted by the Ahmed Kathrada Foundation.

The more things change, the more they stay the same – Jean-Baptiste Alphonse Karr

It has been thirty years since the end of Apartheid in South Africa, yet the freedoms of democracy remain distant for most. The wonderful, world-renowned rights enshrined in the constitution remain fable-like to the poorest, who still have to fight for even the smallest bit of justice and dignity in their daily lives.

The fight over and for land in South Africa spans hundreds of years. Key dates for the conquest and theft thereof include but are not limited to 1652 when the first Dutch settlers arrived on our shores, 1913 when the Land Act formally restricted land ownership of ‘non-white’ peoples (yes, on the tip of Africa, bizarre I know) or 1948 when the ultimate formalisation of exclusion came in the form of Apartheid.

However, the date most people are familiar with when it comes to this country’s history, is 1994, which marked the transition from white minority rule to a fully-fledged democracy. One which was meant to undo the injustices of the past and guarantee basic human rights for all its people.

Sitting in a packed cinema in Johannesburg, at a private screening of Mother City hosted by the Ahmed Kathrada Foundation, one could be forgiven for thinking that for some (read most), despite living in a country governed by ‘their own’, very little had been done to change their fortunes three decades on. The film co-directed by impact filmmaker Miki Redelinghuys and investigative journalist Pearlie Joubert, has been screened to sold-out audiences since it first premiered at the opening night of the Encounters South African International Documentary Festival in June 2024.

Through the life of Reclaim the City campaigner, Nkosikhona “Face” Swartbooi, the story of what dispossession means to those who live and work in the City of Cape Town unfolds over an hour and forty minutes. He narrates his experiences and those of his fellow activists and reclaimers at Ahmed Kathrada House in Green Point and Cissie Gool House in Woodstock. The social movement operates under the slogan: “Land for people not for profit”, and has sustained two of the longest-standing occupations of vacant buildings in the city centre since 2017.

It is not a first-person documentary, but the filmmakers’ intimacy and proximity to the activists makes one experience it as such. The time spent in internal strategy meetings, inside reclaimed buildings, and in public confrontations with politicians helps put viewers in the heart of the fight for affordable social housing in Cape Town. Shot freehand and off the shoulder for the most part, authenticity is quickly established and maintained as the film ebbs and flows through dense legal challenges and heartbreaking personal narratives.

The film confronts the legacy of Apartheid spatial planning, town planning which deliberately and forcefully removed Black, Coloured, Indian and Asian people from city centres and suburbs to the outskirts. Close enough to provide reliable, cheap labour but far enough that when the work was over, they remained out of sight. The areas people were relocated to were often derelict and devoid of access to services – a fact that remains true today.

The people who live in these two buildings are ordinary South Africans who had until the occupation remained financially and physically locked out of formal housing ‘opportunities’ (as the government calls them) by being held on stagnant housing lists. South Africa is one of the most unequal countries in the world, and that still largely manifests itself across racial lines. The monthly minimum wage in the country is about R 5 400 ($315), while the average rental for a one-bedroom apartment in the city of Cape Town is R 9 370 ($547). For anyone who lives outside of the City Bowl, transport ranges between R2 000 ($116) and R4 000 (233) a month. It’s clear that the math ain’t mathing and that this financial exclusion is segregation by another name.

From start to finish, people desperate for change and dignity are met with “be patient” from deflecting politicians, “this is not how it’d done” from irritated locals, and “move, now” followed by undue violence from angry property owners. The housing problem highlighted by activists builds in intensity through their sustained action (occupations and protests) and the city’s inaction as the film comes to a devastating and ultimately fatal climax at the hands of chronic neglect.

One of the most affecting cinematic devices in the documentary is the original score by Edward George King and Charl-Johan Lingenfelder. It swells and quiets in all the right places, making incredibly difficult and traumatic subject matter easier to wade through on the back of its accompaniment. Coupled with the six years of careful and intimate documentation of the movement, this film serves as a witness to the violence of poverty, inequality and systematic racism. It asks those watching to move beyond passivity and indifference about an issue that seemingly doesn’t affect them, to consider human dignity as an unequivocal right they can play an active role in securing for themselves and others.

Screenings of the film are updated regularly: https://www.mothercitydocumentary.com/

Finally developed another roll of film – averaging about a year a roll – lol. Have just bought some more film so hoping to change this habit quite quickly and take my camera along on every adventure, big or small, I embark on in the next few months.

This roll covered quite a bit of ground, it travelled with me to a speed dating event, a road trip and girls’ weekend away in the Vaal, an especially magical few days in Cape Town, a side quest to a botanical garden at a conference in Stellenbosch and a final trip with my class of postgraduate students at Constitutional Hill. Very different but very special memories.

I love how much more selective I am when shooting on film, and which moments feel special enough to etch onto film, I’ve missed the intimacy with memory this brings. Additionally, the imperfection in some of my frames feels almost signature and unshackles me for a moment from the obsessive need to have the right f stop, focus and ISO with each shot – something I am trying to unlearn as I shift between shooting on an SLR and my film camera.

I listened to an full audiobook for the very first time and let me say up front – I actually enjoyed it so much! Before this experience I was a little anti where audiobooks were concerned, imagining that it must be ‘cheating’ and a grating experience akin to listening to the world’s longest podcast. But it was neither of those things.

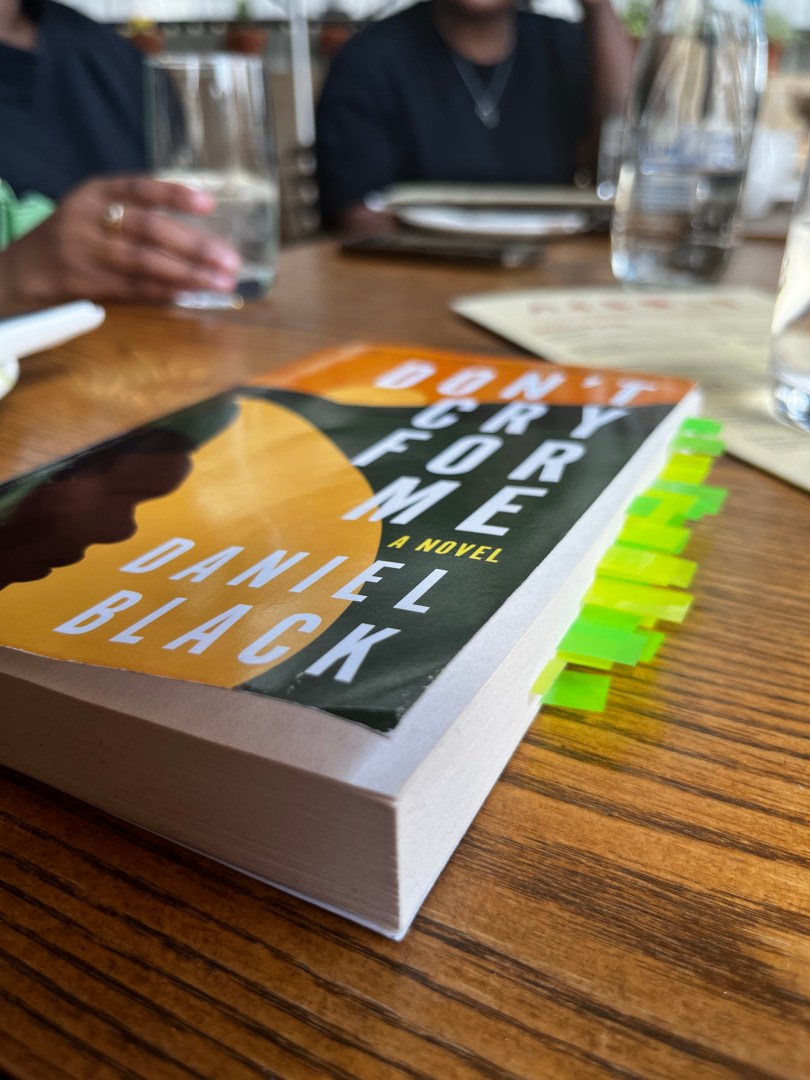

Choosing to listen to this book by Daniel Black rather than read it was a choice driven by convenience, the cost of living crisis and a book club meeting less than a week away. A softcover copy would have set me back R700, while the audiobook was free to listen to Everand with their 30-day free trail (which I forget to cancel and led to a loud ‘FUCK’ in the middle of a set of leg presses at the gym last night when the bank notification popped up) and promised to only take up 7 hours and 28 minutes. And boy did those seven hours fly by – I was THOROUGHLY entertained from the onset and throughout.

Read by the author himself, I noted that the cadences and timing were always spot on, there were one or two audible editing/recording flashes but not noticeable enough to ruin any part of the experience. In a nutshell, this is a tale about a father and son’s complicated relationship, told from the oft times problematic point of view of a dying father. It felt honest in sometimes cringeworthy ways, but I really liked that because that is human. The narrator is deeply flawed and in the parts where he can’t or won’t recognise that in himself, we are afforded the freedom to colour in for ourselves – which is the best part of reading for me. No two people interpret or experience a passage, a chapter, a whole book the same way and that’s so cool to me.

Anyway back to the book, I was particularly struck, again, by just how recent slavery was. That some people and their parents and were raised on plantations within the last 100 years. The periodization makes it easier to understand Jacob as a (by)product of his environment and circumstances. He can’t help but be the man he is, despite sometimes knowing better, acting against that better judgement and honouring his true feelings. It is unfortunately too relatable in parts (domestic abuse, racism, homophobia, sexism – all the ism’s really).

As I listened along, bookmarking some of my favourite bits was really easy on the app, transcribing them for the purposes of this post not as much.

I would love to read this again (or for the first time if we are to be pedantic), really enjoy the exploration of black fatherhood and the level of grace it forces one to extend as a result.