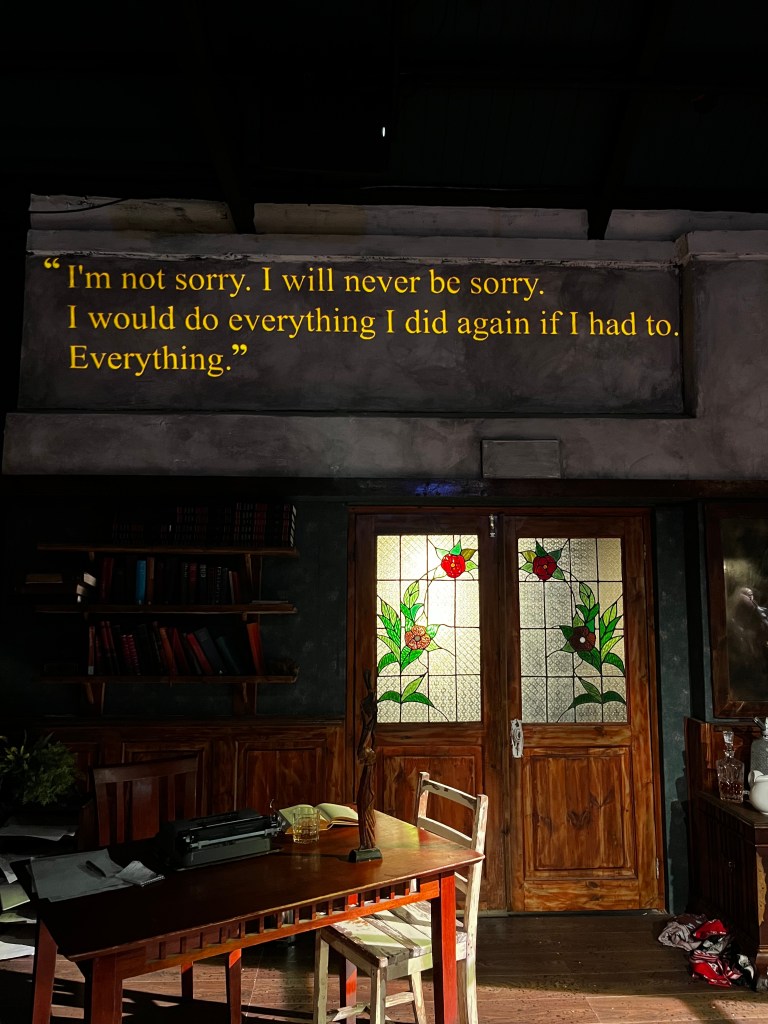

This is the message that reverberated in my being when I came home from watching The Cry of Winnie Mandela at the Market Theatre last month (May 2024).

Adapted from the novel of the same name written by Njabulo S. Ndebele, the play felt like an apparition straight from the book cracked open at the spine. The novel had been sitting on my bookshelf since a random trip to Clarkes in Cape Town with my brother in 2019, leaving the shop that day with the gifted copy I had imagined I would be giving myself over to its contents soon, but life and living happened – until I had just two weeks before curtains up to get stuck in. Luckily for me once I started, I could barely put it down! It is a form bending, intimate and harrowing account of womanhood, loneliness and the alienation of strength (a strength required, not innate).

“I’m fine, but insane.”

– Mamello Molete, page 44

I initially bought tickets based off of who was directing the play alone. Momo Motsunyane. A fire. A force. I have never seen Momo on stage and been left unmoved, close to tears and deliriously joyful all at once, which is how I knew this would be a production that would leave me altered after experiencing it. Walking into the intimate theatre, with the pensive writer pacing and muttering to himself, I knew immediatley that we were about to be transported into another realm.

If I had to describe this book in one word it would be: personal, no intimate. From the very first sentence in the introduction – which is inward looking – to the last – which throws forward to a hopeful future – one is thrust into the inner lives of the writer (Njabulo S. Ndebele) and his characters with their noses pressed up against their insecurities, humiliation, longing, hurt and unwavering affections.

Instead of attempting to write a clear-cut biography of a woman almost “too big” to capture fully, the writer chooses to tell the stories of ‘ordinary’ women and through their telling, begin to peel back the layers of a figure steeped in mystery, shrouded in controversy and shielded by personality. Ndebele also writes the stories of four woman in Apartheid South Africa with a tenderness and rawness that was unexpected but most welcome.

While the stories cover themes from adultery, to sacrifice and even sexual liberation, at their core is one constant theme – abandonment. The women chronicled are alone. Some are alone in their marriages, others alone as extras in the lives of others and one alone in her revolutionary persona. Through no decision-making of their own, their circumstances leave them forever altered by their chronic aloneness and their lives turned into waiting rooms.

“When you are waiting, you know the meaning of desire: the desire to be the only woman (even in a illicit relationship); the desire for secrecy and pleasure of remaining unacught; the desire to prolong intimate moments beyond time and circumstances…”

– Delisiwe S’kosana, page 64

The novel felt like it was written to be performed and this became apparent as it unfolded before me in the Barney Simon theatre. Perhaps this was my own bias having just read the novel before watching, no experiencing it on stage, but it felt less like an adaptation and more of a rendering. The cast made up by Lesley “Les” Nkosi (Professor Ndebele), Rami Chuene (Mmannete Mofolo) Mofolo, Pulane Rampoana (Mamello Molete), Siyasanga Papu (Delisiwe Dulcie S’kosana), and Nambitha Mpumlwana (Winnie Nomzamo Mandela) brought Ndebele’s words and Motsunyane’s vision to life perfectly. Using song, wit and conversation to soften the ‘mbhokoto’s’ on stage.

I appreciate how the novel and the play alike aim to move beyond the historic accounts of stoicism and duty where black women are concerned, and instead asks the audience to consider and contemplate their vulnerabilities and extend them grace. They do the same for one another in their otherworldly conversations between Madikizela-Mandela and Cleopatra. I wish I could have seen it on stage one more time before the run was over, but I guess I will always have the novel to return to.